I have yet to find a script that is as engaging or suspenseful as Christopher McQuarrie’s crime drama, The Usual Suspects. It’s no wonder that McQuarrie won an Academy Award in 1995 for ‘Best Original Screenplay’. This response is going to be an evaluation of the script only. Although the acting and cinematography is excellent in the movie, the script is its own experience that deserves recognition. The script is the foundation; where everything begins

McQuarrie’s attention to detail is outstanding. He finds the perfect balance of dialogue and narrative. Despite what some people believe, a screenplay is not simply all dialogue with a line about the setting here and there. Like a recipe, a successful screenplay should be equal parts dialogue and narrative. We need vivid descriptions of characters and locations to give the dialogue weight and context. In The Usual Suspects, one of the first characters to be introduced is Fred Fenster who is described as a man “dressed conspicuously in a loud suit and tie with shoes that have no hope of matching” (4). Before this character even utters a single word, we immediately understand that this is a person with his own sense of style; an eccentric character with an outward personality to match his appearance. All of this came from one line. The descriptions don’t have to be long, comprehensive paragraphs, just a line or two that leaves a lasting impression in the reader’s mind.

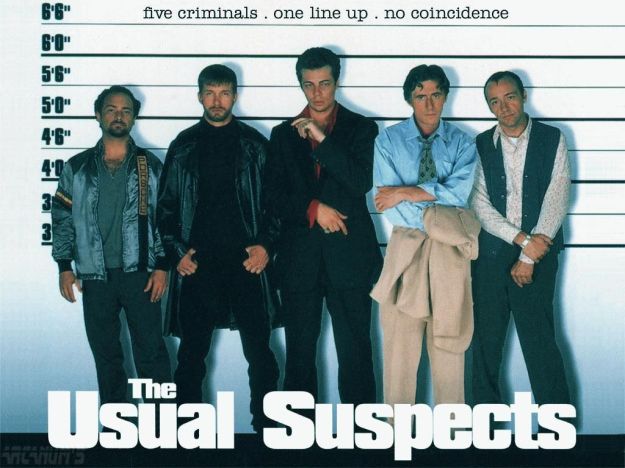

Without spoiling anything, the movie is about a group of five criminals told primarily through flashbacks by one of the members: a man named Roger “Verbal” Kint. People call him Verbal because he “never stops talking” (See! More specific, stand out details). Verbal and the gang were involved in a series of jobs that led up to a shoot-out on a dock. He is one of the only survivors that isn’t in critical condition. The jumping back and forth between the past and present leaves things feeling fresh. Before we can get tired of one story, we are thrown into the other.

McQuarrie holds our attention by keeping the action constant and masterfully building up to the finale. At the start of the script, we are given a description of war torn dock. A man takes a final drag of a cigarette and then there is a gunshot. Not even two pages go by and someone might be dead. This is how you hook an audience. We then learn about the man on the dock, Dean Keaton. Through flashbacks, we see the kind of man that Keaton was before the shoot-out occurs. The action is continued by Verbal recounting the jobs that he and the gang pull off. With each job, the stakes get higher and the conflict grows larger. It propels them further toward the climax of the piece.

Another aspect that this script excels in is having a large, distinguishable cast without confusing characters, which can be difficult to pull off. The script introduces a few characters at a time and lets the audience observe how they act and how they talk. Good characterization is essential here because without it, every character will end up sounding and acting the same. In a script with unique characters, we should be able to read a line of dialogue without looking at the name and be able to tell which character is talking. The characters each have their own distinct voice. The hot-headed and foul mouthed McManus is a completely different character than Keaton who is usually calm and collected.

The dialogue in the script is equally as interesting and unique as the descriptions. Rarely do characters give direct responses to each other. They let their attitudes and subtexts do all the REAL talking. When the intimidating Special Agent Kujan asks Verbal a fairly obvious question, Verbal fires back with blunt, sarcastic answer:

KUJAN

(smiling)

You know a dealer named Ruby Deemer, Verbal?

VERBAL

You know a religious guy named John Paul? (35)

Verbal’s subtext in that line is saying “No shit, Sherlock. Everyone knows Ruby!” Compare that to all the other less interesting but more obvious answers that McQuarrie could have given Verbal: “Yes!” “Maybe…” “I’m not answering.” The trick is to go for the least obvious response possible.

Another area where McQuarrie goes for the less obvious description is when Agent Kujan rushes out of the building into a crowd of people. Instead of simply stating “Kujan bursts out of the office looking dazed,” we get:

“A moment later, Agent David Kujan of U.S. Customs wanders into the frame, looking around much in the way a child would when lost at the circus” (120)

By using this simile the audience can instantly get a vivid image of what’s happening or how a character is acting.

Early on in the script we are introduced to the idea of this criminal mastermind who may or may not exist. Everyone is the script is asking: “Who is Keyser Soze?” Much like “Who is John Galt?” in the novel Atlas Shrugged, the mystery behind this particular character keeps the audience engaged. We learn of Soze’s supposed backstory; his brutality and cunning wit. The gang goes from doing simple heist jobs for Soze to plotting his execution.

The aspects of good storytelling that this script gets right like characterization and specific descriptions are lessons that writers of any genre can take advice from. The only thing that is unique to screenwriting is the rapid pace that scripts must follow to keeps an audience’s interest. But even then, writers can learn how to trim their pieces down and keep only the most essential details that move the story along. It’s possible to turn a good script into a bad movie, but nearly impossible to turn a bad script into a good movie.

Now go be awesome!

Happy Thanksgiving everyone!

-The Critic